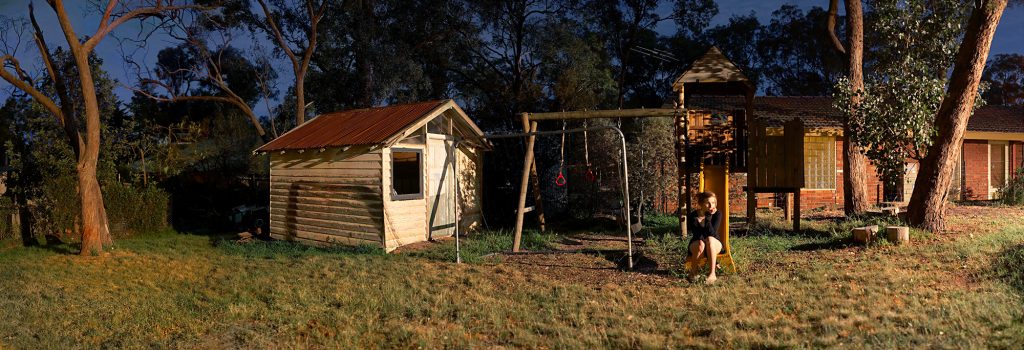

Still Cinema is a series of re-staged scenes about the complexities and intimacies, the longing and contemplation, and the fear and loathing that inhabit contemporary relationships.

These images draw on the intersecting traditions of cinema and photography and investigate how a still, silent photograph can convey the emotion, feeling and narrative power of the cinema.

They take inspiration from the visual iconography, narration, lighting and composition of filmmakers Wong Kar-Wai and David Lynch as way of enacting the unfolding of these stories.

My interest in portraiture, social stereotypes and cultural conventions is both affectionate and critical of a youth culture caught in a moment of transition.

These posed informal portraits are about the state of being with another person but also of being on your own. They continue my engagement with the human subject in popular culture and its social construction. My interest lies in the space between images and feelings, and the personal significance of narrative gestures and unspoken experiences.

Though documentary in appearance, these images are sampled and collaged together. This suggests that both photography and every day life are a form of performance whose authenticity we increasingly question.

These are the in-between moments that define us, our time, and our relationships to one another.

My work addresses issues of identity and personal difference and suggests such contemporary concerns through various visual means: most notably the construction of scenes, and the installation of large scale prints.

I work in the style of Tableau Vivant because I’m not photographing reality, I’m recreating it. Into this strangely familiar but disconcerting world of large scale and immersive photographs I “raid history to help inform our reasoned understanding of the present”. (Crombie 2010:132)

Tableau Vivant is French for ‘living picture’. The term describes a group of actors or models carefully staged or posed, and often theatrically lit. The approach marries the art forms of stage, painting and photography. My Tableau Vivants are narratives about the difficulties of love.

Being abandoned by one, and claimed by another, are not uncommon themes in contemporary relationships. The abandonment of romantic love, the embrace of communal love, and the abyss between them, define much of my creative intentions and artistic inspiration.

References:

Avoiding the Inevitable and other Collisions is primarily concerned with visually representing my experience of the inescapable. These stories without an end attempt to destabilise the figure by placing them in the wrong place at the wrong time, thereby creating tension between what we see and what we feel.

The wide perspectives belittle but don’t destroy the individual. Filled with evidence of social enterprise in the form of bridges and buildings, roads and street lights, they remain vacated or deserted cultural spaces. They show someone in the middle of something, whilst on the edge of something. They remind us that you can still inhabit these spaces on you’re own terms, whatever that may be.

I am not responsible for the ending of these stories. To view these images is to become part of their story, even if we’re not comfortable with it.

I am making really personal work. It is as much about my love of photography as it is about me. I want to be seen as a character in my images and for my images to be read as a narrative about our feelings, thoughts and concerns. That is, the ideas I share with my friends and our culture.

I want my pictures to appear as I see things. This is not about the indexical authority of photography. That doesn’t interest me. What I think I’ve fallen in love with, in Wolfgang Tilmans’ words, is that photographs “usually manipulate and lie about what is in front of the camera but never lie about the intentions behind the camera.” (Bright 2005)

Our psychological relationship between ourselves and our environment is my point of departure in this series. Figures that seem to be at odds with one another, and who inhabit an impenetrable world of their own making. Their purpose and what they are doing remains a mystery. Charged moments burdened with symbolism and meaning, though remaining open to interpretation. Who is calling who? What are they saying? Where is he going? Quiet but disquieting encounters.

“The problem today is that there are too many things to believe in and not enough belief to go around.” (Martin 2009)

The modern individual struggling to come to terms with where they belong.

References:

“Today… the mediascape, is the only ‘nature’ we know.” (Shaviro, 2003:IX)

The idea and arrangement of my work is based on a 1959 Hollywood film titled ‘Pillow Talk’ staring Doris Day and Rock Hudson, which characterises the romantic intervention of analogue technology in personal and social discourse. Fifty years later my generation is just as obsessed with our own ‘pillow talk’, only now we do it with digital technology.

Conversations are what hold us together. Texting, Myspace-ing, Facebook-ing, Twitter-ing connects my unconnected generation and reinforces it’s own culture. Pillow Talk in 1959, with its split screens and popular culture references, was showing us things that couldn’t normally be seen. That is, we couldn’t be in two places at once. It was also showing us what was really going on at the other ‘end of the line’. The film connected people through its formal construction, yet they remain disconnected in the narrative.

Fifty years later, what has really changed? We are still trying to find a space to be together. We still try to understand each other. We are al- ways trying to figure out what the other person is thinking. We connect ourselves while remaining disconnected.

Placing everyone in the same picture connects them and reveals a narrative. The framing shows its conscious construction and references that all meaning is an interpretation, and that even our own story is a construction. This is the same as our hair cuts, our t-shirts and sneakers. They are symbols that acknowledge the construction of meaning in contemporary culture.

“Beautiful.. is an adjective that we often employ to indicate something that we like. In this sense, it seems that what is beautiful is the same as what is good… but also what we should like to have for ourselves… we talk of Beauty when we enjoy something for what it is, irrespective of whether we possess it or not.” (Eco, 2004:9)

In its time, Pillow Talk was also thought of as a beautifully made film, that looked and sounded wonderful, and was embedded in popular culture. I’m also wondering how relevant ‘ideals of beauty’ are in contemporary fine art photography. Are beautiful photographs merely beautiful photographs? Or can they allow us to discuss what role aesthetics has to play in conceptual photography?

References:

I was speaking with a friend of mine the other day and was shocked by her surprise at what her boyfriend had just told her. She had been completely unaware that for the past week he had been thinking of breaking up with her. But in his confession he turned it around saying ‘but if you want to break up with me, that’s alright’.

His insincerity was really a game of appearances; while losing, he was actually winning. The realisation that he really didn’t care at all about her despite showing all the pretensions of being her boyfriend has echoes in many of my other friends and their relationships. People stay in relationships because they’re not sure if they will be ok on their own. These problems plague a lot of people I know.

My photographs are depictions of these stories. They are dual self portraits in the sense that we are on opposite sides of the photographic plane, dealing with our shared expectations, disappointments, hopes and illusions. We stare at each other, hoping for the best. “To my mind, a compelling portrait depends on a mutual readiness to acknowledge personal vulnerability and weakness” (1)

Despite first appearances where everything is sad and lonely, the act of photographing includes the affirmation that we are OK, alone or not. That we do survive, and that we are becoming the people we really are. “The camera connects me to the experience and clarifies what is going on between me and the subject” (2). The photography binds us together, and gives us a reason to be different.

As my friends and I struggle to find our place in the world, certain vows end up being broken, illusions are misplaced, surprises are encountered and expectations are left behind. This process of renegotiation and redefinition, though sometimes painful, sometimes despairing, nevertheless seems right and proper as if it was a play or a game, or a sense of destiny. I hope my images contain remnants of this uncertainty and evidence of the difficulties, but also show hope and resilience, and a belief that such experiences are an investment in one’s self.

My thinking and my photography are dominated by these shifting relationships. As Sally Mann says “There’s the paradox: We see the beauty and we see the dark side of things; the corn fields and the full sails, but the ashes, as well. The Japanese have a word for this dual perception: mono no aware. It means something like “beauty tinged with sadness.” (3)

The critical point of my portraits is that my friends are prepared to reveal themselves to me as the main subject of the photograph. We make a com- mitment as friends and as human beings to the depiction and honest revelation of how we feel. This subjectivity defines the objective limits of our understanding and awareness. If it doesn’t, the image becomes a portrait of something else, an artifice, or at worst a lie.

References:

“Who are you, Face, you who I am, whom I follow, you who look at me without seeing me, you whom I see without knowing whom, you in whom I look at myself, you who would not be without me, you whom I envelope, you who seduce me and into whom I do not enter…” Helene Cixous & Roni Horn, (2008), Roni Horn: A Kind of You, Steidl & Part- ners, Göttingen, Germany.

My world is my friends. Their world is their friends. Together we are trying to work out where we belong. These images are about the spaces within us and the spaces between us.

I’m interested in the fragile nature of happiness, our quests and desires, and how we start or drop out of relationships, with ourselves and each other. I am particularly interested in the journeys that we make and the paths that we take.

I’m photographing things that can’t be seen. I’m photographing feelings, thoughts and emotions that lie in the recesses. My dark prints are not about dark thoughts or dark feelings. Rather it is a case of how little you have to work with, and how much you can suggest with that.

These still and silent images speak loudly about my concerns. They are moments contemplating what might have been, what might be and what will never be.

Faces intrigue us.

Gestures envelope us.

Memories haunt us.

Possibilities evade us.

Photography becomes us.